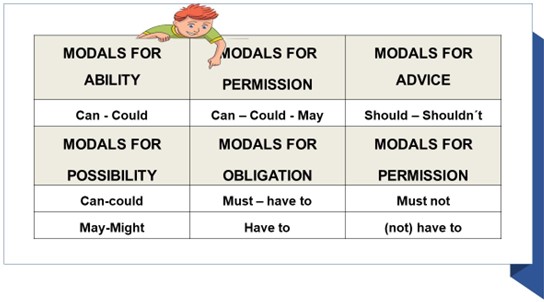

I. WHAT ARE MODAL VERBS?

- These verbs are different from the rest because each one of them has a specific meaning or intention.

- Modal verbs do not have a conjugation. “Have to” is an exception. This verb needs to be conjugated and use auxiliaries do /don´t / does / doesn´t / depending on the context.

- They are always followed by a verb in base form.

Let´s go a little deeper into modal verbs for prohibition.

- SOMETHING IS PROHIBITED _ It is forbidden to perform certain activities. For example:

You must not touch the artwork at the museum

- SOMETHING IS NOT ALLOWED_ An authority has claimed rules that need to be followed. For example:

You must not take pictures with a flash in this room

- IT IS IMPORTANT NOT TO DO SOMETHING_ To maintain the order of situations in context. For instance:

Because of covid, you must not enter the museum without a facemask

- SOMETHING IS NOT NECESSARY TO BE DONE_ If you don't feel like doing something you can skip it and there is no problem with it. For instance:

You don't have to visit all the rooms in the museum today

- TO DO SOMETHING IS OPTIONAL_ You can do something as long as you want to, although you have the option not to do it and it will be OK. For example:

You don't have to come with me to the tour

- NO REPERCUSSIONS_ You are not required to do something you don't want to because it is not urgent

You don't have to read the flyer they gave you at the entrance

- Both MUST NOT and DON´T HAVE TO / DOESN´T HAVE TO are negative expressions, but the first one (MUST NOT) is a command while the second one (DON'T HAVE TO) is a choice.

II. CONSOLIDATION

III. EXERCISE I.

IV. READING TEXT.

READING COMPREHENSION AND VOCBULARY BUILDING

A ‘MUSEUM OF TOLERANCE’ TO REMEMBER INTOLERANCE IN INDIA

(I) In 1993, a multimedia institution called the Museum of Tolerance opened in Los Angeles. In the quarter century of its existence, it has displayed to half a million people annually, the history of hate around the world — the Jewish Holocaust, atrocities in Cambodia, the civil rights movement, among others. At the core of the museum’s conception lay the idea of human rights and equality. Its central premise was, and still is, to inform as graphically as possible, injustices in recent history and remind new generations of the experience of intolerance.

(II) How then does India fare in such lessons? Is there a case to be made for a public display of human rights? It is hard not to see the value of such a therapeutic idea for our own time. In India, where human rights have recently been divided along ethnic and religious lines, the importance of a national institution that gives vent to private prejudices and disputed public correctives, growing religious suspicions and racist intolerance is a much-needed facility. Given the current fear of the other, and the corrosive atmosphere that exists in the country, the value of such a place cannot be overstated. A dispirited and agitated population needs to be drawn into a framework that builds on the memory of the country’s half-forgotten ideals and stated beliefs.

(III) Throughout the world many such museums perform precisely that function. Holocaust museums reveal the extent of Nazi atrocities in ways that resonate with Jewish and non-Jewish visitors. This often includes testimonies of Holocaust survivors; sometimes live volunteers tell their stories. Picture galleries of prisoners, and postcards of children murdered in concentration camps are displayed, even giving details of how the child was killed. In Atlanta, a memorial to African Americans lynched in the southern US describes the gruesome murders on individual plaques. Such graphic presentations — however morbid — are done to educate younger generations and promote a larger understanding of equality and human rights.

(IV) How does the Indian present measure up to the country’s glorious — and often inglorious — past? Merely a recall of India’s great ancient civilization is not enough to assuage the guilt of difficult current and recent events — the Partition, Emergency, Sikh riots, Mandal Commission, Babri Masjid demolition, citizenship law, etc. Political and social events of such magnitude have shaped today’s society and require to be played over and over in the subconscious. Without their reminder the county’s institutions can never be fully tested; without their constant recall, democracy becomes a work in regress, not progress.

(V) The culture of intolerance, communal unrest and other significant actions can be used to enlarge on available histories to enlighten and caution the public. An Indian museum of tolerance will doubtless present facts, but also provoke and engage citizens with the all-important question: what has happened to the country’s inclusiveness? Without evidence it would be hard to explain to future generations born into a Hindu India that at one time, the country had a Sikh Prime Minister and Muslim presidents. Believe it or not, Muslim music celebrated Hindu weddings; lead roles in the Ramayan serial were even played by Muslim actors. It may sound outlandish to future visitors to the museum, but a strange history of cultural co-existence had once made India an enviable example of religious brotherhood. Punjabi Hindu families even raised one of their sons as a Sikh. My own Hindu family has a Muslim uncle, a Sikh aunt, cousins married to Jewish Americans and Catholic Brazilians, with several mixed offsprings. On the rare reunion dinner, such diversity looks like a private UN gathering.

(VI) At a time when ideas of human rights are undergoing transformation, the visibility of their history is an all-important public affair. So far, as a result of not knowing, the wider public sentiment has oscillated between rumour, resentment and quick offence. When information is perverted into private social media, and public engagement takes the form of sporadic street protest and campus politics, little else can be expected. The new museum can act as an important intermediary, a permanent door to living ideals. As the government pushes to create all too new architectural symbols at India Gate, preparing to present a different face to the country before the next election, it hardly needs stating that the value of such a monumental public space is being wasted on a shameless nationalism. Were it made to serve functions of cultural and social value over the mere bureaucratic officialdom currently proposed, the place would become worthy of its open magnificence. A museum that raises fundamental questions about our own public life should be at the center of our public life.

V. PRACTICE I.

VI. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Azar, B. S., Azar, D.A., & Koch R.S. (2009). Understanding and Using English Grammar. Longman.

Barker C. and Mitchell, L. (2004). Mega 1 (First Ed.). Macmillan Publishers.

Hewings, M. (2013) Advanced Grammar in Use with Answers: A Self-Study Reference and Practice Book for Advanced Learners of English. Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, R. (2012). English Grammar in Use. Ernst Klett Sprachen.

Murray, L. (2014) English Grammar. Cambridge University Press.

VII. WEB RESOURCES

Images_Compra propia de licencias de banco de imágenes de Pixton y Pngtree, exentas de derechos de autor. https://www-es.pixton.com/ & https://es.pngtree.com/free-backgrounds.

Reading Text retrieved and adapted from Gautam Bhatia (2020). Wanted: A ‘museum of tolerance’ to remember intolerance in India. The times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/toi-edit-page/wanted-a-museum-of-tolerance-to-remember-intolerance-in-india/_Unless otherwise noted, this content is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

VIII. CREDITS

- All practice exercises and charts were written by _2022_ENES- LEÓN-UNAM

- Audio version performed by Kimberly, Isabella, John and Matt_Compra propia de licencia de uso de voces en Voicemaker, exenta de derechos de autor. https://voicemaker.in/ _Connie Reyes Cruz_2022_